The heartbeat of the Indian economy should not be so difficult to find. Once found, it shouldn’t be so difficult to feel. But since it is both — hard to find and too irregular to feel — there’s a surfeit of doctors doling out diagnosis that are confusing at best and contrasting at worst. The patient is improving and worsening at the same time!

We are, of course, talking about employment — quantity and quality of jobs being created across the country. It’s the matrix to gauge the health of the economy, society and polity of any country, more so in a country with the largest and youngest population in the world. Employment drives everything from income to spending to sales to profits to investment to new jobs and better homes.

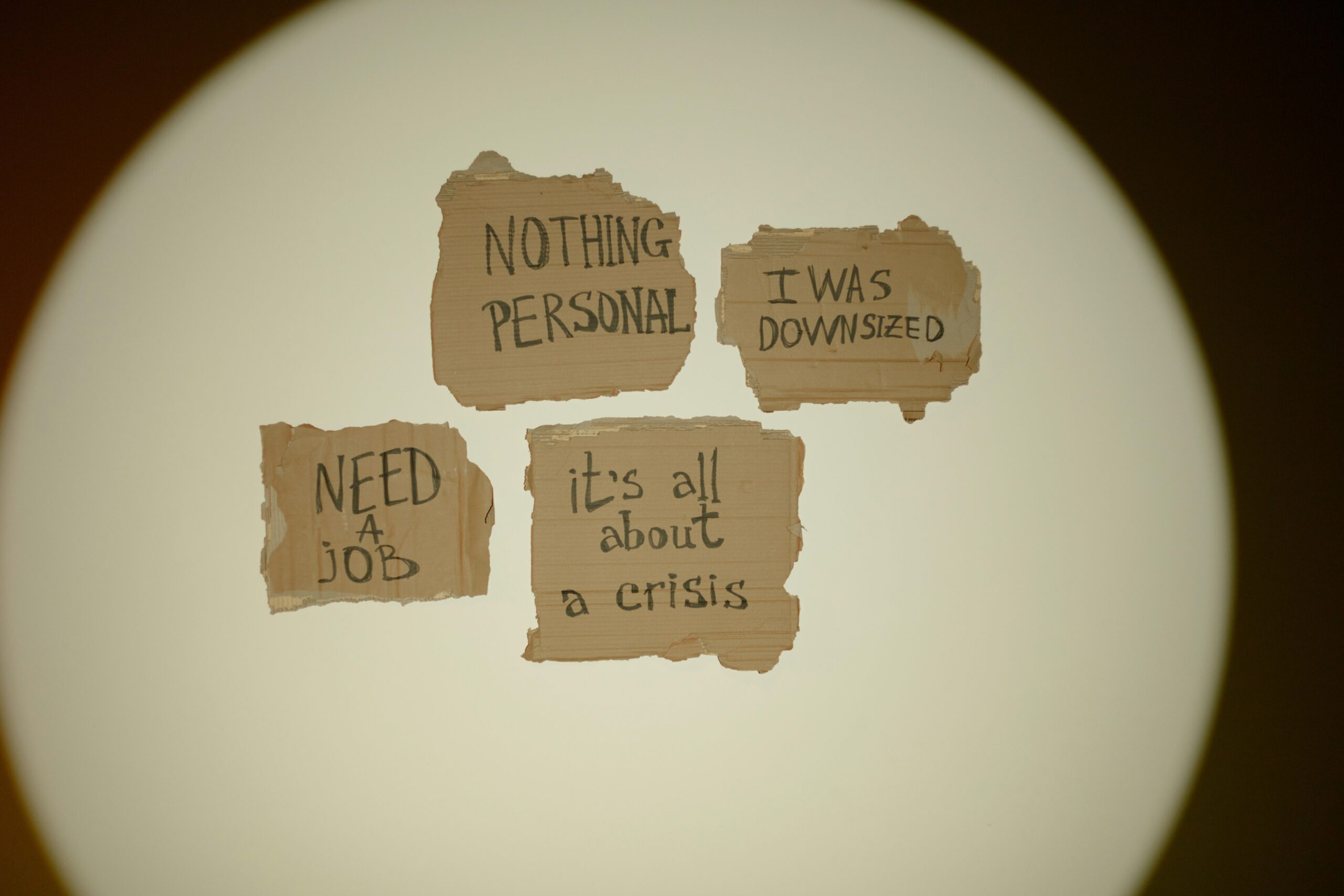

Right now, India could be amid a record jobs boom or an employment crisis — and there are experts and data to sway you in either direction.

Let’s start with the good news. The most report on employment (RBI KLEMS) says India added 4.7 crore new jobs in 2023-24, or 38 lakh each month of the year. This is the highest annual number of jobs created in over four decades tracked by the KLEMS database. This is also the only official jobs data for 2023-2024. So, where’s the doubt?

The survey doesn’t provide a sector-wise break-up of 4.7 crore jobs because it’s a provisional figure. For the previous year’s, RBI’s jobs data is at a considerable variance with the other official collector of employment data: Periodic Labor Force Survey (PLFS). For example, KLEMS says 1.9 crore new jobs were created in 2022-23, while PLFS puts it at 4.1 crore — a difference of 2.2 crore jobs.

The number of new jobs and where they are being created is only the start of the debate, and the confusion. Quality of jobs is next, especially in a country where most of these employed are self-employed and a chunk of them are employed but not paid. You can have a job without work and work without pay. Quality of employment is closely linked to the length of employment. You can be counted as employed for a week if you had work for only one hour on any day of the week. You can also be considered employed for a year if you worked for 30 days in the preceding 12 months. Although most of these counted as employed in a year by PLFS would have had a job for at least six months.

There are huge variations in length and quality of jobs across states. Nearly 30% of youth in Kerala and Goa are without a job, whereas all but 3% of Bihar’s youth are employed. But farm wage in Kerala is 2.5 times that of Bihar. Many of India’s job market issues are not unique. Youth unemployment has been at record highs in Brazil, China, and South Africa. What is perhaps unique to India is the shallow and confused understanding even basics, such as who is employed, for how long, and whether a job pays for a basic minimum living.

ANNUAL, WEEKLY & DAILY STATUS:

USUAL STATUS: Comprises “Principal Status’ and ‘Subsidiary Status’. If a person found work for a ‘relatively long part of 365 days preceding the date of survey, he is considered employed in principal status. Of the remaining, those who had work for at least 30 days in the preceding 365 days are counted as employed in subsidiary status. A person could be doing multiple jobs during a specific period. These two statues are covered in the annual PLFS and the report covering the June-July period is normally released in October every year.

CURRENT WEEKLY STATUS: If a person is employed for at least one hour on any day during the seven days preceding the date of survey, the person is considered employed during the week. Currently weekly status data comes out in two forms — figures covering rural and urban employment are released once a year in the annual report, and separate quarterly data is released only for urban employment through the year.

WORKING FOR SELF: Although manufacturing and farming for self-use is counted as employment, service provided to self isn’t employment.

FREQUENCY: PLFS annual employment data is usually released three months after the end of the year. Quarterly data is released two months from the end of a quarter. In the US, employment data is released in the first month. Every release has monthly, quarterly, 6 monthly and annual statistics.

INDIA AND THE WORLD:

Share of regular employment: In India is exceptionally low even when compared with developing countries. In Brazil, 68% of employed have regular jobs. In China, it’s 54%, and in Russia 93%. India’s figure of 23% is lower even than Bangladesh’s 42%.

A similar disparity exists in share of working women. Till 2018-19, only 24.5% of working-age women were in India. In 2022-23, the figure rose to 37%. In Brazil and China, female labor force participation is 49% and in Russia, it is 49%.

DOLE FOR THE UNEMPLOYED:

- Post-war, Western economies recognized capitalism will frequently create an unemployment and skills mismatch. Answer: unemployment dole – a fixed, smallish payment for those looking for jobs or rendered jobless.

- India doesn’t have universal dole. If it did, non-govt jobs wouldn’t be as unattractive. In part because low wage/poor working conditions in private sector jobs wouldn’t be able to compete with the prospect of free money. More important, losing a private sector job wouldn’t spell disaster. Therefore, the scramble for government jobs would become less.

- How will governments find the money? One way is to rework welfare financing. People with a dole (or jobs) wouldn’t need free grain/free power/free fuel, etc.